|

This section contains 897 words (approx. 3 pages at 400 words per page) |

|

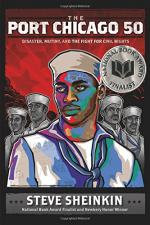

The Port Chicago 50 Summary & Study Guide Description

The Port Chicago 50 Summary & Study Guide includes comprehensive information and analysis to help you understand the book. This study guide contains the following sections:

This detailed literature summary also contains Topics for Discussion on The Port Chicago 50 by Steve Sheinkin.

The following version of this book was used to create this study guide: Sheinkin, Steve. The Port Chicgo 50. Roaring Brook Press, 2014.

The Port Chicago 50 is a historical account by Steve Sheinkin geared toward young readers of World War II and civil rights that details the 1944 Port Chicago disaster, and the ensuing trial in which Joe Small and other black workers refused to return to work under unsafe conditions. The book is told in the third-person past-tense narrative mode, with Sheinkin interrupting the narrative at numerous points for purposes of context and to relay other important information.

When World War II broke out, blacks were very limited to the roles they could play in the United States Armed Forces. Nevertheless, countless African-Americans like Joseph “Joe” Small, Percy Robinson, Robert Routh, and Spencer Sikes enlisted to defend America for various reasons. For example, many wanted to prove themselves capable of combat roles in the military, while others hoped that stellar service would lead to greater rights for blacks in general in America. Facing pressure from civil rights groups and important leaders – both white and black – the U.S. Navy changed its policy to allow blacks to be trained as seamen, though blacks would not be allowed to serve at sea except as mess attendants. The Navy feared that racism and segregation would compromise their ability to win the war.

Despite this, Joe Small and the others in his basic training class still looked forward to serving America, though they were disappointed in being relegated to shore work. They were even more concerned when it was revealed they would be serving at Port Chicago, an isolated installation with a large pier at the end of railroad tracks, where they would be loading live ammunition onto Naval ships. Small was even more concerned by the lack of safety precautions (for example, mattresses were what were used to stop bombs on rail carts from slamming into ships after being unloaded from train boxcars and taken down to the pier), and was disturbed that only black men, supervised by white officers, would be loading the ammunition and bombs onto the ships. There were no whites at all doing the actual loading. Despite their ignored concerns and fears that they expressed to their commander, Lieutenant Delucchi, Small and a few hundred other blacks worked courageously and tirelessly to quickly and efficiently load ships for war.

A few years passed uneventfully. Things suddenly changed on the night of July 17, 1944. Small and his detachment had just bedded down for the night when a massive explosion, followed by an even bigger explosion, rocked Port Chicago. Men scrambled down to the pier, which had been obliterated. Two ships in dock being loaded were destroyed and sunk. Hundreds were dead, their bodies torn apart and unrecognizable. The cause of the explosions was not known, but Small and his men were commended for the way they handled the situation, putting out fires and assisting with rescue efforts. Robert Routh was blinded by the explosion, and sent to the hospital for his injuries. The Navy quickly began investigating the explosion, and though no official blame was placed, many officers at Port Chicago blamed Small and the black loaders, calling them careless and stupid.

On August 11, 1944, Small and the remaining Port Chicago men were ordered back to work loading ammunition at another port. Small and a few hundred others refused to return to work because nothing had changed in terms of safety or the kind of work involved. Various officers attempted to convince the men to return to work, but only when charges of war time mutiny that carry the penalty of death were threatened, did the majority of men return to work. Only Small and 49 others – The Port Chicago 50 – refused. They said they would follow any order except loading ammunition. They knew they were doing the right thing by refusing this order, but the Navy saw otherwise. The men were arrested and tried for mutiny. The judges found them all guilty, and the men were sentenced to 15 years hard labor – a light sentence given the nature of the situation, owed largely to the skill of the defense attorney, Gerald Veltmann.

As Small and his fellows began their prison sentences, Thurgood Marshall, a black civil rights lawyer for the NAACP, along with leaders like Eleanor Roosevelt, took up their cause. They insisted the trial was a farce because the men involved are black, and because they never actually mutinied. At the same time, enormous pressure from blacks and whites alike compelled further integration of the armed forces. It was decided that Small and the others would be released and allowed to serve at sea instead around the same time all military roles were opened up to blacks. Small and the others heroically and ably served out their Naval careers before retiring to successful civilian lives. However, they were haunted for the rest of their lives by the events of the explosion and trial. Small, along with the others, never doubted they did the right thing, no matter how much it cost them. In the 1990s, it was declared that the work loading ammunition that Smalls and the other black men were ordered to do was indeed the result of racism – but convictions of mutiny remain to the present day because no evidence was found of racism in the trial itself.

Read more from the Study Guide

|

This section contains 897 words (approx. 3 pages at 400 words per page) |

|