|

This section contains 4,480 words (approx. 12 pages at 400 words per page) |

|

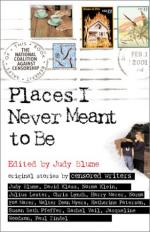

Places I Never Meant to Be: Original Stories by Censored Writers Summary & Study Guide Description

Places I Never Meant to Be: Original Stories by Censored Writers Summary & Study Guide includes comprehensive information and analysis to help you understand the book. This study guide contains the following sections:

This detailed literature summary also contains Topics for Discussion on Places I Never Meant to Be: Original Stories by Censored Writers by Judy Blume.

Judy Blumeappears in Censorship: A Personal View & A Tribute to Norma Klein

Judy Blume is the editor of this collection of stories, and she also wrote the introduction and "A Tribute to Norma Klein" at the end of the collection. As the author of these two additions to the collection, she plays the largest role of anyone in this book other than the censors. As a child, Judy Blume was curious about the adult world. Since her mother forbade her to read "A Rage to Live" by John O'Hara in fifth grade, she was excited to see that her junior high reading list contained any book by John O'Hara. Unfortunately, when she went to the library, the librarian informed her that "A Rage to Live" was on the restricted list so Judy could not borrow the book without her parents' written permission. She was angry at the librarian but never thought that it might not be the librarian's choice. Aside from that one instance, Judy's parents never dictated what she could read, and when she complained about the book being restricted, her aunt leant her a copy that led Judy to read everything she could find by that author. Censorship is defined as forbidding expression believed to threaten political, social or moral order, but Judy wonders what these words mean to writers, their chosen stories, readers and the books they choose to read. Judy began writing in her mid-twenties with "Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret" about her feelings in sixth grade. Not thinking about controversy, she wanted to write the truth and would have never believed that she would become one of the most banned writers in America. The principal of her children's school refused to add the book to the library because it discussed menstruation, while one woman phoned Judy to call her a communist. Judy wrote 13 more books that decade, but her publishers tried to shield her from the negative feedback in hopes she would not be intimidated if she did not know that some people were upset by her work. Though Judy heard about the disapproval, she was not concerned because there was no organized effort to ban her books. She notes that the 1970s were a good decade because writers were free to write about real kids in the real world; however, the censor emerged after the 1980 presidential election with the intent of deciding what all children could read. Seeing books and thinking as dangerous, parents were quick to jump on the bandwagon for fear of "exposing their children to ideas different from their own" (page 5). Schools got rid of anything seen as controversial, their decisions based on what would not offend the censors, not on what was best for the children. Judy's books were constantly challenged and restricted due to the use of curses and topics deemed inappropriate. Her editor wanted her to remove the passage concerned masturbation in "Tiger Eyes" so it would reach as many readers as possible. Judy argued that the moment was important in her character's development, but she eventually caved and removed it. Even now, she recalls how lonely she felt at that moment.

Such a climate has a chilling effect on writers, making it easy to become discouraged. Judy began to speak out about her experiences and was surprised to find she was not as alone as she thought. Her life changed when she learned about the National Coalition Against Censorship and met Leanne Katz who was devoted to defending the First Amendment. Judy goes on to discuss several teachers who were forced to resign from their positions due to their attempts to defend books that they were censored unjustly. This obsession with burning books continues into the twenty-first century: books about Halloween or witches are seen as promoting Satanism while "Romeo and Juliet" is condemned of romanticizing suicide. Judy worries how young people are affected by this loss; they will only be assigned bland books for required reading if no one speaks out for them, causing them not to find the information they need in novels that illuminate life. Censors want to rate books, but individual families should decide what their own children read. This urge no longer comes solely from the religious right. It has spread across the political spectrum. For example, "Huckleberry Finn" is challenged yearly for racial epithets. Judy insists that it is better to discuss the language and why it is appropriate in the context of the book instead of simply banning it. One of Judy's friends refused to allow her children to read "The Stupids Step Out" because she did not want her children to use that word, but Judy wishes she had used it as an opportunity to teach her children why it is hurtful to call another person stupid instead of avoiding the issue. She laments the loss of books that will not be written in this age of censorship as many writers resort to self-censorship. The book is dedicated to Leanne Katz for trying to prevent voices from being silenced. Though many censored writers are missing from this collection, Judy is grateful to those who decided to contribute as they are all writers who have been challenged by groups wanting to forbid their books, and each shares their own experiences with censorship. Not only does censorship happen, it can occur anywhere, even where you least expect it. The first step is awareness. Support groups against censorship can help because censors and school boards hate publicity, yet they will make decisions that affect everyone's First Amendment rights if no one takes a stand. To those who write or want to write, Judy advises "there is no predicting the censor... So write honestly. Write from deep inside" (page 15). Leanne once told Judy that Judy's job is to write as well as she can and Leanne's job is to defend what is written, but Judy warns that Leanne cannot do it on her own; "it's up to all of us" (page 15).

In "A Tribute to Norma Klein", Judy Blume explains that Norma was Judy's first friend who also wrote, and they had a lot in common, including that they both "rushed into reading adult novels at eleven or twelve, to find an alternative to the idealized, sanitized, sentimentalized books meant for readers our ages" (page 195). Judy and Norma met in the early 1970s and bonded on their way to a meeting of children's book writers. Judy was charmed when she read an advance copy of Norma's "Mom, the Wolfman, and Me". A few years later, they found themselves together on the "most censored list". Norma's work was banned because of the nontraditional families she wrote about and because she wrote about young characters' sexuality. Norma tried to write about real life and found nothing objectionable in writing the truth. One of Judy's favorite books by Norma Klein is "Naomi in the Middle" which has been challenged because of the sexual context, and a few years ago, a woman objected to the novel, claiming it promotes alcoholism since the grandmother fixes warm milk laced with rum to get the kids to sleep; this woman does not want anyone telling her children that it is okay to use alcohol. Judy sees this as proof that "when it comes to censorship, if it's not one thing, it's another" (page 196). Norma knew writers who gave up because they became so discouraged, but she charged on, refusing to water down her children's books because she never wrote anything she would not want her own daughters to read. Norma was a prolific writer, and her sudden death in 1989 was shocking. Judy misses her friendship and her voice on the page, and there was no way she could edit a book by censored writers without including Norma Klein. Luckily, her husband found "That Which is Non-Existent" which was originally published in "Focus" literary journal in 1959 when Norma was a student at Barnard College, and this story shows her early promise for creating believable, complicated characters. If Norma were still alive, Judy knows she would be speaking out on the same issues and still encouraging other writers to keep going, full steam ahead.

Censorsappears in Places I Never Meant to Be

Because "Places I Never Meant to Be" is a collection of stories by censored authors, a significant portion of the book is devoted to discussing censors and censorship. Each author gives their own viewpoint on censors after their story. Censorship is defined as forbidding expression believed to threaten political, social or moral order, but Judy Blume wonders what these words mean to writers, their chosen stories, readers and the books they choose to read. She notes that the 1970s were a good decade because writers were free to write about real kids in the real world; however, the censor emerged after the 1980 presidential election with the intent of deciding what all children could read. Seeing books and thinking as dangerous, parents were quick to jump on the bandwagon for fear of "exposing their children to ideas different from their own" (page 5). Censors want to rate books, but individual families should decide what their own children read. To those who write or want to write, Judy advises "there is no predicting the censor... So write honestly. Write from deep inside" (page 15). Norma Fox Mazer notes that the concept of censorship has become wearily familiar. She hopes censorship has not affected her otherwise, but she still has to clear her mind of censorious presences before writing. It is bad for writers and for readers; censorship is crippling. Readers should have the right to pick their own books, and writers need the freedom of their imaginations because that is all they have; letting the censors into their imagination leads to dullness, imitation and mediocrity. In Julius Lester On Censorship, censors fear loss of control because "language can seduce us into forgetting where we are and who we are" (page 52). Sometimes it is difficult to write without censoring himself because he knows there are forces ready to seize upon anything they find objectionable. "Censorship is an attitude of mistrust and suspicion that seeks to deprive the human experience of mystery and complexity" (page 52).

Rachel Vail tries to ignore the pressure to yield to the censor, suggesting those who want to censor "offensive" books should use the offensive literary situation as a platform for discussion with their children instead of banning the book. In Katherine Paterson On Censorship, Katherine Paterson tries not to allow censorship to affect her work because self-censorship is damaging and she knows that she is likely to write a book that does not affect anyone if her chief goal is to not offend. In Jacqueline Woodson On Censorship, people do not always notice when censorship is happening. Sometimes the library just cannot afford a book, but other times are more obvious like the letters that Jacqueline Woodson received from sixth graders objecting to a book she wrote or the illustrator who refused to illustrate a cover because he disapproved of the book. The silence is scary as the person under attack by censorship is usually the last to know. Jacqueline knew people would not like her because of prejudice from a young age, but she did not know the many ways that hatred could exist or that it would enter into the "most sacred part of me-my writing" (page 83). As a child and young adult, Jacqueline wrote for herself, and she has gone back to that beginning and again found solace in writing. The hatred will always be there, but so will writing. The writing gives her a better sense of the world and helps her to grow and understand. Harry Mazer fears caution more than the censors because he must be able to write the book he wants to write. "The Last Mission" was challenged by a school board in Minnesota because of the language and removed from shelves, but Mazer believes "that if we want to read about the real world we also must accept the language of that world" (page 97). Some of his other books were also removed because of language. Censorship is always negative, but there are positive outcomes from the challenges because the issues are brought out in the open and many respond that they do not want censors trying to force their views on everyone else's kids. Some books are removed or simply not ordered without protest, and this type of closet censorship is difficult to gauge so Mazer is unsure if they are winning or losing against the censors. Good books are created when authors can write freely, but the quality of work suffers when an author writes to the standard of the feared censor. Books belong to all readers, and more books and authors are needed to represent various points of view. "Books are our windows on the world. They permit us to safely experience other lives and ways of thinking and feeling. Books give us a glimmer of the complexity and wonder of life. All this, the censor would deny us" (page 98).

Walter Dean Myers believes that many African-American writers confine their topic matters solely to issues concerning the black experience in America because of restraints placed on them that is censorship by omission and prevents many from writing. Susan Beth Pfeffer was the assistant literary editor at her school paper during her senior year of high school when a writer was forbidden to run a certain editorial. Pfeffer combined this with another incident about a high school newspaper that her friend told her about years later when she became a writer of young adult novels. It is easy to censor written work, but it is impossible to censor a mind, an imagination or the future. David Klass notes that teens want to read books that depict real life situations; "I feel very strongly that students do not need to be protected from books. People should learn to choose books for themselves, based on their own tastes and talents" (page 140). His characters seem to exist on their own as he writes, and he tries to follow them; he cannot truthfully render characters if he is constantly concerned with offending the censors. In Paul Zindel On Censorship, someone has always wanted to censor Paul Zindel since he started writing, but he believes most art arouses a degree of censorship since it is just on the other side of decency and able to shock for a while. It began with him censoring himself out of a desire to hide who he was, but his father censored him by abandoning the family when Zindel was two years old, and his mother wanted to censor anything that contained family secrets. As a professional writer, editors helped Zindel "obscure a darkness from my first drafts and balance it with laser bursts of compassion and understanding" (page 162). He continued self-censoring with his first book, "The Pigman", and was shocked when a librarian threatened to quit if "The Pigman" was added to the shelves. Luckily, her supervisors insisted that the book would be available to young people. Zindel's work is shocking because of his ideas, not because of individual words. He ignored censorship for a long time because he thought that a small amount of controversy was fashionable. He has since been exposed to the "CensorKooks", and he cannot imagine the rituals of some adults who try to inflict pure madness on schools and libraries by censoring books. Zindel notes that those on the front lines who face such attacks do an excellent job of protecting him and other writers. When he is called on to confront a CensorKook, he reminds them that kids are often capable of guiding themselves away from unsuitable material. He also believes that parents have the right to decide what their kids read but not what other kids read. He notes that CensorKooks tend to be megalomaniacs showcasing for the media, but when people tire of them, sanity can move forward and dispatch them. He also uses a very apt and entertaining metaphor to compare the "CensorKooks" to vampires.

Chris Lynch thought there was some mistake when his first book was challenged, but he figured he was hanging out with a better class of undesirables when he learned that Judy Blume was also being challenged. He changed his mind when he realized that people were challenging the right for his book to exist and wanted to preclude any debate. The title of Lynch's "He-Man Women Haters Club" was challenged because women hating is unfashionable, but the idea of the series is to illuminate the absurdity of male posturing. Still, people refused to open the book in order to understand the purpose of the title. Lynch considered changing the title, but he could not; he needed to "believe that there was room for the writer to be a little bit risky in trying to get his message across with impact" (page 183). He insists that there needs to be an override philosophy to guide writers through dealing with such challenges. Judy Blume notes that both she and her friend, Norma Klein, were censored in the 1970s for various reasons. Judy sees this as proof that "when it comes to censorship, if it's not one thing, it's another" (page 196). Norma knew writers who gave up because they became so discouraged, but she charged on, refusing to water down her children's books because she never wrote anything she would not want her own daughters to read. If Norma were still alive, Judy knows she would be speaking out on the same issues and still encouraging other writers to keep going, full steam ahead.

Sarabethappears in Meeting the Mugger

Sarabeth is the main character of "Meeting the Mugger". She is a teenage girl who is impatient with her mother's advice. This impatience leads her to run out of the house one night and wander into a part of the city where she is mugged. Her jacket is stolen, and her back gets cut up. At home, she tells her mother about the mugging after everyone else leaves, and Mom holds and comforts her. The next day, Sarabeth agrees to wear Mom's jacket if Mom goes to the doctor to check out the odd freckle on her leg. Later, Sarabeth only remembers the time with her mother after the mugging because the doctor finds cancer. After Mom's death, Sarabeth goes to live with Leo, Mom's ex-boyfriend, and his new girlfriend, Pepper. She still listens to her mother's advice.

Janieappears in Meeting the Mugger

Janie is Sarabeth's mother. Her advice causes her daughter to become impatient, but after Sarabeth rushes from the house one evening and gets mugged, Janie comforts her daughter. The next day, Sarabeth agrees to wear Mom's jacket if Mom goes to the doctor to check out the odd freckle on her leg. The doctor finds cancer everywhere; Janie dies.

Leoappears in Meeting the Mugger

Leo is Janie's boyfriend who leaves her for Pepper. After Janie's death, Sarabeth lives with Leo and Pepper.

Spear AKA Adrianappears in Spear

Spear is the main character of "Spear". He is a black senior in high school whose father was a black leader whose anti-white speeches caused race riots in the 1970s. He is the class president at his school, and when his friends mock a white girl, Norma, for taking their African-American Literature class, Spear befriends her and eventually falls in love with her. Unfortunately, her parents learn about their relationship and transfer her to an all-white school. Spear resigns as class president and insists on people calling him Adrian. He is happy with his new anonymity. He talks to Norma about once a week.

Norma Jean Rayappears in Spear

Norma Jean Ray is the white girl who takes Spear's African-American Literature course. They begin spending more time together and fall in love, though Norma objects to Spear's love because her family is racist and his people need him. Norma's parents force her to transfer to an all-white school when they learn about her relationship with Spear, but she still calls Spear once a week and tells him she loves him.

Jodyappears in Going Sentimental

Jody is the main character and narrator of "Going Sentimental". She loses her virginity to her boyfriend, Mackey, of four years, but afterward, she feels indifferent and worries why she suddenly cares about romance and passion. Mackey appears in the stands during her basketball game with a sign that reads "Happy Birthday Aunt Tillie", mimicking what she said during their first time together.

Mackeyappears in Going Sentimental

Mackey is Jody's boyfriend who she loses her virginity to. He worries about his performance and that she feels differently toward him after their encounter. Mackey appears in the stands during Jody's basketball game with a sign that reads "Happy Birthday Aunt Tillie", mimicking what she said during their first time together.

Claytena Smallsappears in July Saturday

Claytena Smalls is friends with the narrator of "July Saturday". She has a huge crush on Chuck Williams and comforts him after his family's house burns down.

Chuck Williamsappears in July Saturday

Chuck Williams is friends with the narrator of "July Saturday". He probably would have asked Claytena Smalls out today if his house had not burned down. Claytena tries to comfort Chuck after the event.

Aaron Hillappears in You Come, Too, A-Ron

Aaron Hill is the narrator and main character of "You Come, Too, A-Ron". He is an older kid in the foster system, and he returns to Placement in hopes of finding a family because he does not like attending school at Oakmont. While at Placement, he befriends and protects a younger kid, Kenny, and ultimately decides to return to Oakmont so he can talk to Kenny on the phone and visit him on weekends.

Kennyappears in You Come, Too, A-Ron

Kenny is the younger kid at Placement who attaches himself to Aaron after Aaron defends him from some of the older girls. Though a family wants to take Kenny home, Kenny does not want to leave Aaron and agrees only after Aaron promises to call him and visit him.

Johnappears in The Beast Is In the Labyrinth

John is the main character and narrator of "The Beast Is In the Labyrinth". He attends college in Millersville, PA because he wants to escape his home in Harlem, but he visits home for Christmas and Spring Break, as well as to help his mother search for his sister, Temmi. At home, he feels lost in the labyrinth. During Spring Break, John visits Temmi in the hospital and thinks it is too hard to see her in such a condition. He stays to bury her after she dies, and then he returns to Millersville.

Ashleigh AKA Ashesappears in Ashes

Ashleigh is the narrator and main character of "Ashes". Ashleigh visits her father, a dreamer, who tells her he has come upon some financial troubles and owes dangerous people $200. Ashleigh's father asks her to borrow the money from her mom's emergency stash in a teapot. Ashleigh is torn about whether to take her mother's money, but she can hear her father telling her how special she is as she debates with herself.

Rogerappears in Baseball Camp

Roger is the pitcher that does not do well at the team's first scrimmage, and before of this, Paul Creese mocks and taunts him. Roger does not come to practice for several days during which he contacts his father, a big-shot lawyer from New York, who calls the camp and has Paul Creese fired. Paul laments the fact that Roger is a squealer because Roger has the most talent of any of the other ball players and could have really become a pitcher.

Paul Creeseappears in Baseball Camp

Paul Creese is the coach that trains the group of teenagers at baseball camp. He warns them that they will hate him, and he is true to his word. When Paul mocks Roger's pitching and degrades him in front of the other campers, Roger contacts his father, a lawyer, who gets Paul fired. Paul laments the fact that Roger is a squealer because Roger has the most talent of any of the other ball players and could have really become a pitcher.

Tuesday Racinskyappears in Love and Centipedes

Tuesday Racinsky is the main character in "Love and Centipedes". She has a crush on Kyle Ecneps, her science project partner and Maureen Willoughby's boyfriend. When Maureen asks Tuesday to help come up with a prom theme and begins torturing Tuesday's animals, Tuesday fears Kyle has told Maureen something to make her jealous. As Maureen attempts to kill the fish that Tuesday is using for her science project, Tuesday pushes the transformer into Maureen's throat and orders the centipedes in her basement to attack Maureen. She decides to alert the authorities, knowing that no one will believe Maureen's version of events.

Maureen Willoughbyappears in Love and Centipedes

Maureen Willoughby is a popular cheerleader in "Love and Centipedes" who dates Kyle Ecneps. She becomes jealous after learning that Tuesday rubbed Kyle's foot, so she asks Tuesday for help coming up with an idea for a prom theme. At Tuesday's house, she kills Tuesday's turtle and ferret, but Tuesday prevents her from killing the fish she and Kyle are using for their science project by shoving the transformer into Maureen's throat.

Paulyappears in Lie, No Lie

Pauly is the best friend and worst enemy of the narrator in "Lie, No Lie". He convinces the narrator to go to the gym on Valentine's Day which leads to the narrator receiving oral sex from another man in the shower of the locker room. On the way home, Pauly claims he thought he was doing his friend a favor because his friend would not know if he was gay. Still, Pauly calls his friend a deviate and forbids him to touch him.

Benappears in Something Which Is Non-Existent

Ben is the main character of "Something Which is Non-Existent". He befriends Michael, and the two spend a lot of time studying together until Michael begins dating Clara, a girl from his literature class who Ben dislikes. In his room after a brief conversation with Michael and Clara, Ben thinks "it will never matter if I do anything again or not" (page 194), so he types a two-page treatise on the meaning of friendship and reads it while he takes a bath. In the hallway afterward, a boy asks if Ben is alright because he heard him talking to himself, and Ben decides that what he wrote is garbage, chuckling to himself as he returns to his room.

Michaelappears in Something Which Is Non-Existent

Michael is the boy that Ben befriends, and they spend a lot of time together until Michael begins dating a girl from his literature class, Clara, causing Ben to question their friendship.

Read more from the Study Guide

|

This section contains 4,480 words (approx. 12 pages at 400 words per page) |

|