|

This section contains 757 words (approx. 2 pages at 400 words per page) |

|

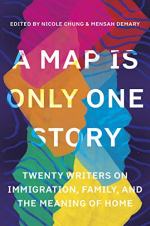

A Map Is Only One Story Summary & Study Guide Description

A Map Is Only One Story Summary & Study Guide includes comprehensive information and analysis to help you understand the book. This study guide contains the following sections:

This detailed literature summary also contains Topics for Discussion on A Map Is Only One Story by Nicole Chung.

The following version of this book was used to create the guide: Chung, Nicole and Mensah Demary, ed. A Map Is Only One Story. Catapult, 2020.

A Map Is Only One Story is a collection of twenty essays that share personal stories of migration, immigration and one’s search for identity in a new country. In “Why We Cross the Border in El Paso,” Victoria Blanco watches the natural force of the Rio Grande River in her youth become a dry riverbed in her adulthood. This swift change mirrors the natural flow of people from El Paso, Texas to Juarez, Mexico becoming like the more hard-edged steel mesh fence erected between the two countries. Jamila Osman’s “A Map of Lost Things” is a search for where she belongs—the Somalia of her parents, the Portland of her youth, the anywhere, nowhere and in-between that exists on the maps of the world. While citizens of some countries find it easy to obtain visas and extended stays, Deepti Kapoor explains in “My Indian Passport is a Bitch” that easy movement between countries is a privilege.

Both Kenechi Uzor and Lauren Alwan become critical of their stay in the United States. Uzor, originally from Nigeria, writes in “This Hell Not Mine” that the free and affluent United States spoken about in Nigeria was radically different than the one he encounters. For Uzor the U.S. contains rules and regulations for everything and people hold an errant notion that Africa is filled with sad case stories of poverty and abuse. Alwan, an Arab-American, is critical of the political policies of Muslim bans that increase fear and hate crimes. She is also subtly critical of the way her grandparents, in order to fit into American society, assimilated and gave up much of their Arab culture.

The essay “How to Write about Your Ancestral Village” is a humorous look at children of immigrants who feel they must travel back to their ancestral country to find a piece of their identity and warns that they will not find what they are looking for. In “Carefree White Girls, Careful Brown Girls,” Cinelle Brown is at first appalled at her instructor’s brazen white privilege, then she hopes she lives a carefree life for both of them. Nur Naseen Ibrahim recounts a family trip from Pakistan to the town of his grandfather’s youth in India before the Partition of 1947. Beyond the militarized border, he finds the land and people similar to Pakistan.

Krstal A. Sital divulges the daily fear of living undocumented in a country and the sense that no one documented could ever understand the stress. Shing Yin Khor’s graphical essay “Say It With Noodles” depicts her growing respect for the language of food, which, like music, can cross language barriers. Sharine Talor recounts Patois, a dialect shared by her Jamaican grandmother, and how it helps her heritage to survive.

In “The Dress” Sorayo Membreno realizes that her upward mobility in the United States means that there will be a part of her life her parents will never be a part of, and that she still has many unwritten rules to learn of this new country. Nina Le Coomes begins to understand how to be comfortable in a body that moves and looks half-Japanese and half-American in “What Miyazaki’s Heroines Taught Me.” The author Kamna Muddagouni learns she has used the phrase “I’m sorry” as a stand-in for how she really feels, especially about the difference she felt as a young immigrant in Australia. Nadia Owusu is upset at the wailers who feign sorrow at her father’s death, compounding her own uncertainty about where she will live and what the future holds.

Jennifer S. Cheng explains her poetry collection “Letters to Mao” portraying Mao as a ghost-like family member in the household despite being thousands of miles from China. Niina Pollari’s family moves to Florida from Finland, and she ends up spending a great deal of time with friends as her young parents enjoy parties by the pools in the apartment complexes. Natalia Sylvester tries to understand how to mourn a grandfather that she hardly knows in “Mourning My Birthplace.” Bix Gabriel asks the readers “Should I Apply for Citizenship?” because, after 20 years of working in the United States, she still is unsure. In “How to Write Iranian America; Or, The Last Essay” Porchista Khakpour relates that even if successful, an immigrant writer second-guesses herself and wonders if she should be writing something other than her heritage.

Read more from the Study Guide

|

This section contains 757 words (approx. 2 pages at 400 words per page) |

|