|

This section contains 1,061 words (approx. 3 pages at 400 words per page) |

|

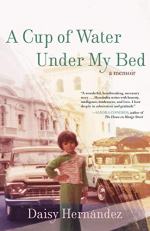

A Cup of Water Under My Bed Summary & Study Guide Description

A Cup of Water Under My Bed Summary & Study Guide includes comprehensive information and analysis to help you understand the book. This study guide contains the following sections:

This detailed literature summary also contains Topics for Discussion on A Cup of Water Under My Bed by Daisy Hernandez.

The following version of this book was used to create this study guide: Hernández, Daisy. A Cup of Water Under My Bed. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014.

A Cup of Water Under My Bed is a memoir consisting of three parts and 10 chapters, plus a prologue and epilogue. The chapters can be read as autonomous essays, though the memoir as a whole proceeds in a roughly linear format through Daisy Hernández's life.

In the prologue, “Condemned” (xi), Hernández recalls a town official coming to her New Jersey home when she was a child and declaring that her family's home should be condemned.

Part I begins with “Before Love, Memory” (3), in which Hernández recalls attending kindergarten and elementary school and learning English. This is challenging because she is surrounded by Spanish speakers—most notably her Colombian mother and aunts, Tía Dora, Tía Rosa, and Tía Chuchi, and her Cuban father. She begins to feel alienated from her family because they are speaking different languages. In adulthood, she develops an interest in returning to her roots and signs up for a Spanish class.

In “Stories She Tells Us” (21), Hernández recalls bedtime stories her mother used to tell about her own life. Alicia Hernández moves to Bogotá, Colombia's capital, at 16. She gets a job at a factory and a coworker encourages her to emigrate to the United States. She borrows money from her sister to do so, and upon arrival in New Jersey, she gets another factory job. Soon after, she meets the author's father, Ygnacio. Thinking about these stories in retrospect as an adult, Hernández realizes that her mother is much stronger, more courageous, and more intelligent than she has given her credit for.

In “The Candy Dish” (35), Hernández turns to her father. During her childhood, he is a heavy drinker and is sometimes verbally and physically abusive. Tía Chuchi tells Hernández that her father practices the Afro-Cuban religion Santería. He leaves offerings for the god Elegguá in a candy dish in the shed behind their house. In adulthood, Hernández learns more about this religion and takes part in a ritual with her father. She feels that understanding his religion has helped her understand him as a person.

In “A Cup of Water Under My Bed” (53), Hernández writes of seeing tarot card readers frequently while growing up, and of the blend of religious and cultural beliefs she was exposed to. When she has nightmares, her mother tells her to place a cup of water under her bed to ward off bad energy or spirits. As an adult, Hernández visits a cowrie shell reader in San Francisco. The man's wife tells her that she was not alone when she was a child contending with abuse from her father—that the god Elegguá was with her.

Part II begins with “Even If I Kiss a Woman” (73), in which Hernández recalls realizing she was bisexual in college. When she tells her mother and aunts that she is dating women, they are upset and refuse to talk to her.

In “Queer Narratives” (89), Hernández writes of volunteering with an LGBTQ+ organization and visiting high school classrooms to talk about her experience. Hernández learned about bisexuality in an eighth grade health class in the context of a conversation about AIDS, and she wants the students she meets to have a different perspective about LGBTQ+ people than she had growing up. Interspersed with these memories, Hernández tells the story of Gwen Araujo, a young transgender woman who was murdered in 2004 by two men she was seeing romantically when they discovered she had been born male. Hernández feels a connection to Gwen because they are both Latina members of the LGBTQ+ community from New Jersey and because she dates transgender men and worries that they could become victims of violence like Gwen.

In “Qué India” (105), Hernández focuses on one of her mother's sisters, Tía Dora. When Tía Dora first came to the U.S. from Colombia she was ill; a doctor diagnosed her with Chagas, a parasitic disease, and recommended surgery. In the years that followed, she continued to be chronically ill and more operations followed. Growing up, when Hernández does something her aunt finds rude, Tía Dora calls her “una india” (108)—an Indian. Hernández is disturbed by her aunt's casual racism and considers how the racist attitudes of those around her contributed to her own discriminatory thoughts and behavior. When Hernández comes out as bisexual, Tía Dora does not speak to her for seven years. Eventually, they reconcile, but Tía Dora continues to express homophobic views. Hernández does not challenge her aunt as aggressively about these views as she might want to because she wishes to keep her aunt in her life.

Part III begins with “Only Ricos Have Credit” (119). Hernández recalls struggling to manage her finances during and after college. She signs up for several credit cards and amasses a considerable amount of debt. In retrospect, she realizes that growing up in a working class immigrant family distorted her feelings about money and material objects and that she often feels she has to buy things in order to fit in with her white peers.

In “My Father's Hands” (135), Hernández recalls her parents' employment and income precarity while she was growing up and the expectations they placed on her to succeed and pursue work in a white collar industry.

In “Blackout” (149), Hernández writes about working for the New York Times. She is bothered by the explicit and implicit racial biases of her white coworkers and by the evidence of economic and racial disparities she observes in the city while reporting on crimes and tragedies. She chooses to leave the job, though she worries that her parents will not understand her decision.

In the epilogue, “Después” (173), Hernández recalls moving to San Francisco and getting a job at ColorLines, a magazine focused on issues of significance to communities of color. She returns to New Jersey when Tía Dora suffers heart failure and passes away. In San Francisco, Hernández feels she has found a home in the Mission neighborhood, where most residents are Latinx and the women remind her of her mother and aunts.

Read more from the Study Guide

|

This section contains 1,061 words (approx. 3 pages at 400 words per page) |

|