The loyalists triumphed in the state election on September 4, 1861, and on that date the California crisis was safely passed. The contest, to be sure, had revealed about twenty thousand anti-Union voters in the state, but the success of the Union faction restored their feeling of self-confidence. The pendulum had at last swung safely in the right direction, and henceforth California could be and was reckoned as a loyal asset to the Union. Such expressions of disloyalty as her secessionists continued to disclose, were of a sporadic and flimsy nature, never materializing into a formidable sentiment; and, adding to their discouragement, the failure of the Confederate invasion of New Mexico in 1862, was no doubt an important factor in suppressing any further open desires for secession.

Sumner was not called East until the October following the election. His removal of course caused keen regret along the coast; but Colonel George Wright, his successor in charge of the Department of the Pacific, proved a masterful man and in every way equal to the situation. In the long run, Colonel Wright probably was as satisfactory to the loyal people of California as General Sumner had been. The five thousand troops were not detailed for duty in the South. Like the first detachment of fifteen hundred, their efforts were directed mainly to protecting the overland mails and guarding the frontier[22].

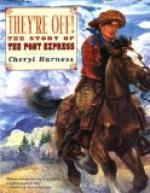

Throughout this crisis, news was received twice a week by the Pony Express, and, be it remembered, in less than half the time required by the old stage coach. Of its services then, no better words can be used than those of Hubert Howe Bancroft.

It was the pony to which every one looked for deliverance; men prayed for the safety of the little beast, and trembled lest the service should be discontinued. Telegraphic dispatches from Washington and New York were sent to St. Louis and thence to Fort Kearney, whence the pony brought them to Sacramento where they were telegraphed to San Francisco.

Great was the relief of the people when Hole’s bill for a daily mail service was passed and the service changed from the Southern to the Central route, as it was early in the summer. * * * Yet after all, it was to the flying pony that all eyes and hearts were turned.

The Pony Express was a real factor in the preservation of California to the Union.

[15] Bancroft.

[16] lbid.

[17] After the War had started, Gwin deserted California and the Union and joined the Confederacy. When this power was broken up, he fled to Mexico and entered the service of Maximilian, then puppet emperor of that unfortunate country. Maximilian bestowed an abundance of hollow honors upon the renegade senator, and made him Duke of the Province of Sonora, which region Gwin and his clique had doubtless coveted as an integral part of their projected “Republic of the Pacific.” Because of this empty title, the nickname, “Duke,” was ever afterward given him. When Maximilian’s soap bubble monarchy had disappeared, Gwin finally returned to California where he passed his old age in retirement.