Skipper Simms paid no attention to him. His eyes swept aloft to the upper deck. There he saw a wide-eyed girl and a man looking down upon them. He wondered if she was the one they sought. There were other women aboard. He could see them, huddled frightened behind Harding and Norris. Some of them were young and beautiful; but there was something about the girl above him that assured him she could be none other than Barbara Harding. To discover the truth Simms resorted to a ruse, for he knew that were he to ask Harding outright if the girl were his daughter the chances were more than even that the old man would suspect something of the nature of their visit and deny her identity.

“Who is that woman you have on board here?” he cried in an accusing tone of voice. “That’s what we’re a-here to find out.”

“Why she’s my daughter, man!” blurted Harding. “Who did you—”

“Thanks,” said Skipper Simms, with a self-satisfied grin. “That’s what I wanted to be sure of. Hey, you, Byrne! You’re nearest the companionway—fetch the girl.”

At the command the mucker turned and leaped up the stairway to the upper deck. Billy Mallory had overheard the conversation below and Simms’ command to Byrne. Disengaging himself from Barbara Harding who in her terror had clutched his arm, he ran forward to the head of the stairway.

The men of the Lotus looked on in mute and helpless rage. All were covered by the guns of the boarding party—the still forms of two of their companions bearing eloquent witness to the slenderness of provocation necessary to tighten the trigger fingers of the beasts standing guard over them.

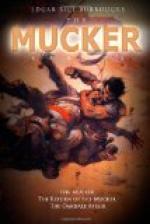

Billy Byrne never hesitated in his rush for the upper deck. The sight of the man awaiting him above but whetted his appetite for battle. The trim flannels, the white shoes, the natty cap, were to the mucker as sufficient cause for justifiable homicide as is an orange ribbon in certain portions of the West Side of Chicago on St. Patrick’s Day. As were “Remember the Alamo,” and “Remember the Maine” to the fighting men of the days that they were live things so were the habiliments of gentility to Billy Byrne at all times.

Billy Mallory was an older man than the mucker—twenty-four perhaps—and fully as large. For four years he had played right guard on a great eastern team, and for three he had pulled stroke upon the crew. During the two years since his graduation he had prided himself upon the maintenance of the physical supremacy that had made the name of Mallory famous in collegiate athletics; but in one vital essential he was hopelessly handicapped in combat with such as Billy Byrne, for Mallory was a gentleman.

As the mucker rushed upward toward him Mallory had all the advantage of position and preparedness, and had he done what Billy Byrne would have done under like circumstances he would have planted a kick in the midst of the mucker’s facial beauties with all the power and weight and energy at his command; but Billy Mallory could no more have perpetrated a cowardly trick such as this than he could have struck a woman.