Rynason thought about that. He tried to remember the minds he had touched during the linkage with Horng: Tebron, the ancient warrior-king, and the young Hirlaji staring at the buildings of one of the ancient cities, and the old, dying one who had decided not to plant again one year ... and Horng himself, tired and calm on the edge of the Flat, amid the ruins of a city. He remembered the others in that crumbling last home of an entire race ... slow, quiet, uncaring.

“I don’t think they’ll do anything. They wouldn’t see any point to it.” He paused, remembering. “They lost all their purpose eight thousand years ago,” he said quietly.

Manning grunted. “Somehow I lack your touching faith in them.”

“And somehow,” Rynason said, “I lack your burning ambition to find an enemy, a handy menace to crush. You argue too hard, Manning.”

Manning raised an eyebrow. “I suppose I haven’t even put a doubt in your mind about them? Not one doubt?”

Rynason turned away and didn’t answer.

Manning sighed. “Maybe it’s time I went out there myself and had a seance with the horses.” He set down his glass of brandy, which he had been turning in his hand as he spoke. “Lee, I want you to check back here with me in two hours ... by then I should have things straightened up and ready to go.”

He strode to the supply closet at one end of the room and took from it a belt and holster, from which he removed a recent-model regulation stunner. “This is as powerful a weapon as we have here so far, except for the heavy stuff. I hope we never have to use any of that—clearing it for use is a lot of red tape.” He looked up and saw the cold expression on Rynason’s face. “Of course, I hope we don’t have to use the stunners, either,” he said calmly.

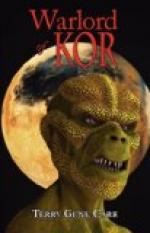

Rynason turned without a word and went to the door. He stopped there for a moment and watched Manning checking over the weapon. He was thinking of the disintegrators he had seen on the steps of the Temple of Kor, and of the shell of a body tumbling out of the shadows.

“I’ll see you at 600,” he said.

SEVEN

Rynason spent the next two hours in town, moving through the windy streets and thinking about what Manning had said. He was right, in a way: this was no more than a foothold for the Earthmen, a touchdown point. It wasn’t even a community yet; buildings were still going up, prices varied widely not only between landings of spacers but also according to who did the selling. A lot of the men here were trying some mining out on the west Flat; their findings had so far been small but they brought the only real income the planet had so far yielded. The rest of the town was rising on its own weight: bars, rooming houses, laundries, and diners—establishments which thrived only because there were men here to patronize them. Several weeks before a few of the men had tried killing and eating the small animals who darted through the alleys, but too many of those men had died and the practice had been quickly abandoned. And they had noticed that when those animals foraged in the refuse heaps outside the town, they died too.