“My great-grandfather used to say to his wife, my great-grandmother, who in turn told it to her daughter, my mother, who repeated it to her daughter, my own sister, that it was a very great art to talk eloquently and well, but an equally great one to know the right moment to stop. I therefore shall follow the advice of my sister, thanks to our mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother, and thus end, not only my moral ebullition, but my letter.”

His playful tenderness lavished itself on his wife in a thousand quaint ways. He would, for example, rise long before her to take his horseback exercise, and always kiss her sleeping face and leave a little note like the following resting on her forehead: “Good-morning, dear little wife! I hope you have had a good sleep and pleasant dreams. I shall be back in two hours. Behave yourself like a good little girl, and don’t run away from your husband.”

Speaking of an infant child, our composer would say merrily, “That boy will be a true Mozart, for he always cries in the very key in which I am playing.”

Mozart’s musical greatness, shown in the symmetry of his art as well as in the richness of his inspirations, has been unanimously acknowledged by his brother composers. Meyerbeer could not restrain his tears when speaking of him. Weber, Mendelssohn, Rossini, and Wagner always praise him in terms of enthusiastic admiration. Haydn called him the greatest of composers. In fertility of invention, beauty of form, and exactness of method, he has never been surpassed, and has but one or two rivals. The composer of three of the greatest operas in musical history, besides many of much more than ordinary excellence; of symphonies that rival Haydn’s for symmetry and melodic affluence; of a great number of quartets, quintets, etc.; and of pianoforte sonatas which rank high among the best; of many masses that are standard in the service of the Catholic Church; of a great variety of beautiful songs—there is hardly any form of music which he did not richly adorn with the treasures of his genius. We may well say, in the words of one of his most competent critics:

“Mozart was a king and a slave—king in his own beautiful realm of music; slave of the circumstances and the conditions of this world. Once over the boundaries of his own kingdom, and he was supreme; but the powers of the earth acknowledged not his sovereignty.”

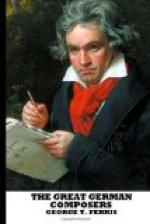

BEETHOVEN.

I.

The name and memory of this composer awaken, in the heart of the lover of music, sentiments of the deepest reverence and admiration. His life was so marked with affliction and so isolated as to make him, in his environment of conditions as a composer, a unique figure.

The principal fact which made the exterior life of Beethoven so bare of the ordinary pleasures that brighten and sweeten existence, his total deafness, greatly enriched his spiritual life. Music finally became to him a purely intellectual conception, for he was without any sensual enjoyment of its effects. To this Samson of music, for whom the ear was like the eye to other men, Milton’s lines may indeed well apply: