It was in the promise of this exhilaration that the seductiveness of the dreaded tones lay.

Even his kindly old physician, diagnosing the pallor of his cheeks and melancholy in his eyes as “a touch of malaria,” added a note of insistence to the voice, as he prescribed that panacea of the day, “a mint julep before breakfast.”

Yet he still sternly and stoutly turned a deaf ear to the voice of the charmer, while dejection drew him deeper and deeper into its depths until one day he found he could not write. His pen seemed suddenly to have lost its power. He sat at his desk in the office of the Messenger with paper before him, with pens and ink at hand, but his brain refused to produce an idea, and for such vague half-thoughts as came to him, he could find no words to give expression.

He was seized upon by terror.

Had his gift of the gods deserted him? Better death than life without his gift! Without it the very ground under his feet seemed uncertain and unsafe!

Then he fell. Driven to the wall, as it seemed to him, he took the only road he saw that led, or seemed to lead, to deliverance. He yielded his will to the voice of the tempter, he tasted the freedom, the exhilaration, the wild joy that his imagination had pictured—drank deep of it!

And then he paid the price he had known all along he would have to pay, though in the hour of his severest temptation the knowledge had not had power to make him strong. Neither, in that hour, had he been able to foresee how hard the price would be. That shadowy, yet very real other self, his avenging conscience, in whose approval he had so long happily rested, arose in its wrath and rebuked him as he had never been rebuked before. It scourged him. It held up before him his bright prospects, his lately acquired and enviable social position, assuring him as it held them up, of their insecurity. It pointed with warning finger to the end of the rainbow and the road leading to it seemed to have suddenly grown ten times longer and rougher than before.

Finally it held up the images of his two good angels, “Muddie,” with her heart of oak, and her tender, sorrow-stricken face, and Virginia, whose soft eyes were a heaven of trustful love—whose beauty, whose purity and innocence, the stored sweets of whose nature were for him alone, and to whom he was as faultless, as supreme as the sun in heaven.

It was too much. The dejection into which his “blue devils” had cast him was as nothing to the remorse that overwhelmed him now. On his knees before Heaven he confessed that his last estate was worse than his first, and cried aloud for forgiveness for the past and strength for the future.

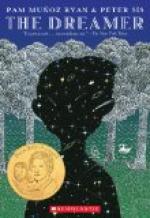

In this mood he sat down to write to Mr. Kennedy (who had been absent upon a summer vacation when he left Baltimore) a letter of acknowledgment for his benefactions—for whatever The Dreamer was, it is very certain that he was not ungrateful.