spared? Yet I had something worth doing to do

in the world!’ Most touching is that sigh, even

more touching than the signs of greatness in his soul,

for it suddenly breathes an anguish long controlled.

It is a human weakness—our own weakness—that

is at last confessed, on the eve of a Passion, as in

the Divine example. At rare times such a question,

in the constant sight of death, in fatigue and weariness,

in the long distress of rain and mud, checks in him

the impulse of life and of spiritual desire. He

was himself the young plant of which he writes, growing,

creating fragrance and breaking into flower, sure

of God, feeling Him alive within itself. But

all at once it knows frost is coming and the threat

of unpitying things. What if the universe were

void, what if in the infinity of the exterior world

there were nothing, across the splendid vision, but

an insensate fatality? What if sacrifice itself

were also a delusion? ’Dark days have come

upon me, and nothingness seems the end of all, whereas

all that is in my being had assured me of the plenitude

of the universe.’ And he asks himself the

anxious question, ’Is it even sure that moral

effort bears any fruit?’ It is something like

abandonment by God. But that darkening of his

lights passes quickly away. He comes again to

the regions of tranquil thought, and leaves them thenceforward

only for the work in hand. ‘I hope,’

he writes, ’that when you think of me you will

have in mind all those who have left everything behind,

and how their nearest and dearest think of them only

in the past, and say of them, “We had once a

brother, who, many years ago, withdrew from this world."’

How strange is the serenity of these lofty thoughts,

how entirely detached from self and from all human

things is this spirit of contemplation. Two slight

traits give us signs: One night, on a battlefield

‘scattered with fragments of men’ and with

burning dwellings, under a starry sky, he makes his

bed in an excavation, and lies there watching the

crescent moon, and waits for dawn; now and again a

shell bursts, earth falls about him, and then silence

returns to the frozen soil: ’I have paid

the price, but I have had moments of solitude full

of God.’ Again, one evening, after five

days of horror (’we have no officers left—they

all died as brave men’), he suddenly comes upon

the body of a friend; ’a white body, splendid

under the moon. I lay down near him.’

In the quietness, by the side of the dead man, nothing

remains but beauty and peace.

* * * * *

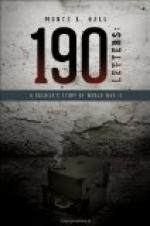

These letters are to be anonymous, at least so long as any hope remains that he who was lost may return. It is enough to know that they were written by a Frenchman who, in love and faith, bore his part in the general effort, the common peril, glad to renounce himself in the pain and the devotion of his countrymen. By a happy fortune that he did not foresee when he left his clean solitude for the sweat, the servitude,