“She’s friends with him already, same as Lizzie was. I wish I knew how to—” But her wish she only sighed, she did not put it into words.

“Never mind the flowers now, little maid; here’s granny inside waiting for us.” Then he put her down on her feet, and led her over the threshold.

Patience, dabbing the tears from her eyes with her handkerchief, stepped forward to meet them. “I’d begun to wonder what had become of ’ee, father,” she said. “I s’pose the train was late. Well, dear,” stooping to kiss her little grandchild, “how are you? Have you got a kiss for granny?”

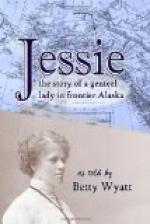

“Yes,” Jessie nodded gravely, “and my face is very clean,” she added, as she put it up to be kissed. But she turned and slipped her hand into her grandfather’s again as soon as the kiss was given, for she felt a little awed and shy with this granny, who seemed so much more grown-up and stern than did the grandfather.

Her shyness did not last very long, though; by the time granny had taken her up to her room and shown her the rose-bush, and taken off her hat and brushed out her hair, and brought her down to tea and lifted her into her seat at the table, much of her shyness had worn off, and the sight of the mug with pictures on it, and the little plate “with words on it,” loosened her tongue again, and set it chattering quite freely.

The meal lasted a long time that night, for Jessie was full of talk, and neither her “granp,” as she already familiarly called him, nor her granny could bear to interrupt her, especially after she had slidden down from her high seat at the table, and clambered on to her grandfather’s knee; for to them her presence seemed like some wonderful dream, from which they were afraid of waking.

At last, though, the little tongue grew quiet, the dark curly head fell back on granp’s shoulder, and then the bright eyes closed.

“I reckon I’d best carry her right up to bed,” said Thomas softly. “If I hand her over to you she’ll waken, as sure as anything.”

Patience only nodded, she could not speak, her heart was so full, and rising she followed him up the stairs, carrying the lamp. At the door of Lizzie’s old room she expected him to stop and hand the sleeping child over to her, but, apparently without remembering what room it was, he walked straight in, and very tenderly laid his burthen on the bed. Then, with a glance at the rose-bush on the sill, he crept softly out and down the stairs again.

Patience stood by her little sleeping grandchild with tears of joy in her eyes. “She’s broke his will,” she said gladly, “for her sake he’s forgotten. P’raps now he’ll get over the trouble, and forget, and be happier again.”

CHAPTER III.

SHOPPING AND TEAING.

The next morning some of Jessie’s shyness had returned, but it vanished again at the sight of the mug with the pictures and the plate with the “words” on it. At the liberal dishful of bacon and eggs she stared wide-eyed.