Rex’s deep laughter broke into the dignified sentences at this point.

“I see you remember.” Judge Rush smiled benignly. “Well, Mr. Fairfax, Billy made an amusing story of that evening. Only the family were at the table and he spared himself not at all. He had been in Orange the day before, and the young lady in the case had told him how you had protected him at your own expense—he made that funny too, but I thought it very fine behavior—very fine, indeed, sir.” Rex’s face flushed under this. “And as I thought the whole affair over afterwards, I not only understood why you had failed me, but I honored you for attempting no explanation, and I made up my mind that you were the man we wanted. Yes, sir, the man we want. A man who knows how to deal with the situations of to-day, with the vices of a great city, that is what we want. I consider tact, and broad-mindedness and self-sacrifice no small qualities for a minister of the gospel; and a combination of those qualities, as in you, I consider exceptional. So I went to this vestry meeting primed, and I told them we had got to have you, sir—and we’ve got to. You’ll come?”

The question was much like an order, but Rex did not mind. “Indeed, I’ll come, Judge Rush,” he said, and his manner of saying it won the last doubtful bit of the Judge’s heart.

The Sunday morning when the new assistant preached his first sermon in St. Eric’s, there sat well back in the congregation a dark-eyed girl, and with her a tall and powerful young man, whose deep shoulders and movements, as of a well fitted machine, advertised an athlete in perfect form. The girl’s face was rapt as she followed, her soul in her eyes, the clean-cut, short sermon, and when the congregation filtered slowly down the aisles she said not a word. But as the two turned into the street she spoke at last.

“He is a saint, isn’t he, Billy?” she asked, and drew a long breath of contentment.

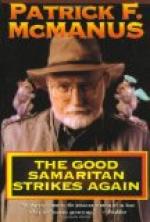

And from six-feet-two in mid-air came Billy Strong’s dictum. “Margery,” he said, impressively, “Rex may be a parson and all that, but, to my mind, that’s not against him; to my mind that suits his style of handling the gloves. There was a chap in the Bible”—Billy swallowed as if embarrassed—“who—who was the spit ‘n’ image of Rex—the good Samaritan chap, you know. He found a seedy one falling over himself by the wayside, and he called him a beast and set him up, and took him to a hotel or something and told the innkeeper to charge it to him, and—I forget the exact words, but he saw him through, don’t you know? And he did it all in a sporty sort of way and there wasn’t a word of whining or fussing at him because he was loaded—that was awfully white of the chap. Rex did more than that for me and not a syllable has he peeped since. And, you know, the consequence of that masterly silence is that I’ve gone on the water-wagon—yes, sir—for a year. And I’m hanged if I’m not going to church every Sunday. He may be a saint as you say, and I suppose there’s no doubt but he’s horrid intellectual—every man must have his weaknesses. But the man that’s a good Samaritan and a good sport all in one, he’s my sort, I’m for him,” said Billy Strong.