CHAPTER I

A Perilous Ride

“I trust no harm has happened to my father, Jacques. The night grows late and there are strange rumours afloat. ’Tis said that the Guises are eager to break the peace.”

“Better open warfare than this state of things, monsieur. The peace is no peace: the king’s troops are robbing and slaying as they please. Francois of the mill told me a pretty tale of their doings to-day. But listen, I hear the beat of hoofs on the road below.”

“There are two horses, Jacques, and they approach very slowly. My father does not usually ride like that.”

“No, faith!” said Jacques, with a laugh; “if his horse went at that pace the Sieur Le Blanc would get down and walk! But the travellers are coming here, nevertheless. Shall we go to the gate, monsieur?”

“It may be as well,” I answered. “One can never tell these days what mischief is brewing.”

By the peasantry for miles around my home was called the Castle of Le Blanc. It stood on the brow of a hill, overlooking a wide plain, and was defended by a dry moat and massive walls. A score of resolute men inside might easily have kept two hundred at bay, and more than once, indeed, the castle had stood a regular siege.

According to Jacques it might have to do so again, for in that year, 1586, of which I write, France was in a terrible state. The nation was divided into two hostile parties—those who fiercely resisted any changes being made in the Church, and the Huguenots, those of the Religion—and the whole land was given over to brawling and disorder.

My father, who was held in high esteem by the Huguenot party, had fought through three campaigns under Gaspard de Coligny, the Admiral, as men, by virtue of his office, generally called him. Severely wounded in one of the numerous skirmishes, he had returned home to be nursed back to health by my mother. Before he recovered a peace was patched up between the two parties, and he had since remained quietly on his estate.

He it was who, rather to my surprise, now came riding at a foot pace into the courtyard. The stranger accompanying him sat his horse limply, and seemed in some danger of falling from the saddle.

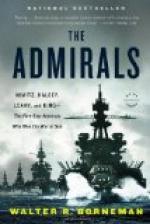

[Illustration: “The stranger accompanying him sat his horse limply.”]

“Take the bridle, Jacques,” cried my father. “Edmond, let your mother know I am bringing with me a wounded man.”

When we had assisted the stranger into one of the chambers I saw that he was of medium height, spare in figure, but tough and sinewy. He had a swarthy complexion, and small, black, twinkling eyes that gave the impression of good-humour. His right arm, evidently broken, was carried in a rough, hastily-made sling; his doublet was bloodstained, and his forehead had been scored by the slash of a knife.

He must have been suffering agony, yet he did not even wince when my father, who had considerable experience of wounds, set the broken limb, while I, after sponging his face with warm water, applied some salve to the gash. But he kept muttering to himself, “This is a whole night wasted; I must set out at daybreak.”