These stains, although their brilliancy may perhaps decay with time, being thus fixed in the flesh, are of course indelible, just as much as the marks of a similar nature which our own sailors frequently make on their arms and breasts, by introducing gunpowder under the skin. One effect, we are told, which they produce on the countenances of the New Zealanders, is to conceal the ravages of old age. Being thus permanent when once imprinted, each becomes also the peculiar distinction of the individual to whom it belongs, and is probably sometimes employed by him as his mark or sign manual. An officer belonging to the “Dromedary,” who happened to have a coat of arms engraved on his seal, was frequently asked by the New Zealanders if the device was his “amoco.” When the missionaries purchased a piece of land from one of the Bay of Islands chiefs, named Gunnah,[X] a copy of the tattooing on the face of the latter, being drawn by a brother chief, was affixed to the grant as his signature; while another native signed as a witness, by adding the “amoco” of one of his own cheeks.

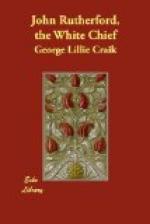

[Illustration: Moko on woman’s lips and chin.

Moko on man’s face.

Names of lines in order of incision— 1. Kau-wae (13) 2. Pere-pehi (7) 3. Hupe (15) 4. Ko-kiri (9) 5. Koro-aha (10) 6. Puta-ringa (12) 7. Po-ngia-ngia (4) and Tara-whakatara (5) 8. Pae-pae (11), Kumi-kumi (6), and Wero (8) 9. Rerepi (3) 10. Ti-whana (1) and Rawha (2) 11. Ti-ti (14) 12. Ipu-rangi (16)]

This is certainly a more perfect substitute for a written name than that said to have been anciently in use in some parts of Europe. In Russia, for example, it is affirmed that in old times the way in which an individual generally gave his signature to a writing was by covering the palm of his hand with ink, and then laying it on the paper. Balbi, who states this, adds that the Russian language still retains an evidence of the practice in its phrase for signing a document, which is roukou prilojite, signifying, literally, to put the hand to it. It may be remarked, however, that this is a form of expression even in our own country; although there is certainly no trace of the singular custom in question having ever prevailed among our ancestors. Whatever may be the fact as to the Russian idiom, our own undoubtedly refers merely to the application of the hand with the pen in it. Each chief appears to be intimately acquainted with the peculiarities of his own “amoco.”

There is also in the possession of the Church Missionary Society a bust of Shungie, cut in a very hard wood by himself, with a rude iron instrument of his own fabrication, on which the tattooing on his face is exactly copied.

The tattooing of the young New Zealander, before he takes his rank as one of the warriors of his tribe, is doubtless also intended to put his manhood to the proof; and may thus be regarded as having the same object with those ceremonies of initiation, as they have been called, which are practised among some other savage nations on the admission of an individual to any new degree of honour or chieftainship.