F.B. Hubbard was the man selected to pull off the “rough stuff” and at the same time keep the odium of crime from smirching the fair names of the conspirators. He was told to “perfect his own organization”. Hubbard was eminently fitted for his position by reason of his intense labor-hatred and his aptitude for intrigue.

The following day the Centralia Daily Chronicle carried the following significant news item:

BUSINESS MEN OF COUNTY ORGANIZE

Representatives From Many Communities Attend Meeting in Chamber of Commerce, Presided Over Secretary of Employers’ Association.

“The labor situation was thoroughly discussed this afternoon at a meeting held in the local Chamber of Commerce which was attended by representative business men from various parts of Lewis County.

“George F. Russell, Secretary of the Employers’ Association, of Washington, presided at the meeting.

“A temporary organization was effected with F. B. Hubbard, President of the Eastern Railway & Lumber Company, as chairman. He was empowered to perfect his own organization. A similar meeting will be held in Chehalis in connection with the noon luncheon of the Citizens’ Club on that day.”

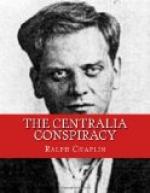

[Illustration: “Special Prosecutor”

C.D. Cunningham, attorney for F.B. Hubbard and various lumber interests, took charge of the prosecution immediately. He was the father of much of the “third degree” methods used on witnesses. Vanderveer offered to prove at the trial that Cunningham was at the jail when Wesley Everest was dragged out, brutally mutilated and then lynched.]

The city of Centralia became alive with gossip and speculation about this new move on the part of the employers. Everybody knew that the whole thing centered around the detested hall of the Union loggers. Curiosity seekers began to come In from all parts of the county to have a peep at this hall before it was wrecked. Business men were known to drive their friends from the new to the old hall in order to show what the former would look like in a short time. People in Centralia generally knew for a certainty that the present hall would go the way of its predecessor. It was just a question now as to the time and circumstances of the event.

Warren O. Grimm had done his bit to work up sentiment against the union loggers and their hall. Only a month previously—on Labor Day, 1919,—he had delivered a “labor” speech that was received with great enthusiasm by a local clique of business men. Posing as an authority on Bolshevism on account of his Siberian service Grimm had elaborated on the dangers of this pernicious doctrine. With a great deal of dramatic emphasis he had urged his audience to beware of the sinister influence of “the American Bolsheviki—the Industrial Workers of the World.”

A few days before the hall was raided Elmer Smith called at Grimm’s office on legal business. Grimm asked him, by the way, what he thought of his Labor Day speech. Smith replied that he thought it was “rotten” and that he couldn’t agree with Grimm’s anti-labor conception of Americanism. Smith pointed to the deportation of Tom Lassiter as an example of the “Americanism” he considered disgraceful. He said also that he thought free speech was one of the fundamental rights of all citizens.