|

This section contains 1,069 words (approx. 3 pages at 400 words per page) |

|

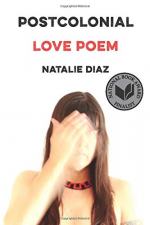

Postcolonial Love Poem Summary & Study Guide Description

Postcolonial Love Poem Summary & Study Guide includes comprehensive information and analysis to help you understand the book. This study guide contains the following sections:

This detailed literature summary also contains Quotes and a Free Quiz on Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalie Diaz.

The following version of this book was used to create this study guide: Diaz, Natalie. Postcolonial Love Poem. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2020.

The collection begins with the title poem, in which the poet recalls numerous unspecified wars and describes herself crossing a desert, ravaged by thirst, to reach her beloved, and states that someday in the future it will rain and the desert will be flooded.

Part I begins with “Blood-Light,” in which Diaz writes of her brother experiencing an episode of delusional thinking and attempting to stab her and their father. She sympathizes with his mental health issues and imagines he has good intentions despite his violent threats. In “These Hands, If Not Gods,” Diaz imagines her hands moving over her lover as similar to God's hands when he created the world. “Catching Copper” is a poem of personification in which she writes of her brothers owning a bullet that is like a pet, which they walk around on a leash. This poem is about the pernicious threat of violence in Native American communities. In “From the Desire Field,” Diaz introduces the setting of the desire field as a symbol for her late-night insomniac worries, explaining that she wanders across it all night, sleepless and anxious, unless she has sex with her lover. In “Manhattan Is a Lenape Word,” Diaz describes the loneliness and sadness she feels while contemplating the Native American lives lost due to genocide and the ongoing violence and marginalization against Natives by the U.S. government. In “American Arithmetic,” she explains that Native Americans are more likely to be killed by police per capita than any other race. In “They Don't Love You Like I Love You,” she recalls her mother discouraging her from getting involved romantically with a white person, using this memory as a metaphor for the marginalization and discrimination Native Americans experience in the predominantly white society of the United States. In “Skin-Light,” Diaz describes her own body and her lover's body as vessels of light and sex as a release from the constricting worries of everyday life. In “Run'n'Gun,” she recalls learning to play basketball on the reservation as a child with her brother and cousin and other young people. They delighted in being able to beat the white players at the local rec center, but as time passed, Diaz's brother stopped playing well because of his addiction issues and her cousin died of a heroin overdose.

Part II begins with “Asterion's Lament,” in which Diaz describes her desire for her lover while comparing herself to the Minotaur from the Greek myth of Theseus. In “Like Church,” Diaz compares Native attitudes about sex and spirituality to those of white American society. In “Wolf OR-7,” she writes of a wolf tracked by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife through California as it sought a mate, comparing this movement to her own desire for her lover. In “Ink-Light” she describes desire through a scene in which she is walking through a snowy evening with her lover. In “The Mustangs,” Diaz recalls the sense of freedom she felt while watching her brother's high school basketball team complete warm-up drills before a game. “Ode to the Beloved's Hips” is about the poet having sex with her female lover. “Top Ten Reasons Why Indians Are Good at Basketball” is a somewhat satirical poem in which Diaz lists humorous possible reasons that Native Americans excel at this sport. In “That Which Cannot Be Stilled,” Diaz recalls being called a “Dirty Indian” (42), and how this slur made her feel inferior. She imagines throwing those who would level such slurs at Native Americans into the sea. In “The First Water Is the Body,” Diaz describes the Mojave belief that the waters of the Colorado River run through the bodies of members of the tribe—a belief that she finds difficult to truly explain to people who are not Mojave.

Part III begins with “I, Minotaur,” in which Diaz once more imagines herself as the Minotaur and expresses her appreciation of her lover's acceptance of her, despite her more difficult feelings like anger and sadness. In “It Was the Animals,” Diaz describes an incident in which her brother came to her house declaring he had a piece of Noah's Ark. Diaz recognized the piece of wood as a fragment of a picture frame, but then imagined a parade of animals entering her house. In “How the Milky Way Was Made,” Diaz imagines lifting the salmon and other animals out of the Colorado River and placing them into the sky where they would not have to suffer the ill effects of the river's contamination. In “exhibits from the American Water Museum,” Diaz conceives of a museum memorializing water, writing of incidents past, present, and future in which colonizers and their descendants have depleted or destroyed water sources as a means of harming marginalized populations. In “Isn't the Air Also a Body, Moving,” Diaz watches a hawk fly overhead in the desert and contemplates anger and how it places a burden on the person feeling it. In “Cranes, Mafiosos, and a Polaroid Camera,” Diaz recalls her brother calling her while she was away on a retreat, asking for help putting his Polaroid camera back together. He had taken it apart because he believed the mafia had planted a transmission device inside it.

In “The Cure for Melancholy is to Take the Horn,” Diaz imagines herself as a horned beast who is tamed by her lover. In “Waist and Sway,” she recalls a former lover, comparing her to a cathedral she looks up at from below. In “If I Should Come Upon Your House Lonely in the West Texas Desert,” she imagines herself as a cowboy arriving at a lover's house and roping the lover with a lariat. She then goes inside the house, living a life of domestic bliss. In “Snake-Light,” Diaz writes of the Mojave's belief in a connection between their people and the rattlesnake, an animal for which they have tremendous respect. In “My Brother, My Wound,” Diaz imagines her brother stabbing her with a fork and then climbing inside of her.

The collection closes with “Grief Work,” in which Diaz writes of the grief she has contended with all her life and imagines dunking her lover under the water of the Colorado River. When they emerge from the river, Diaz feels “clean” and “good” (94).

Read more from the Study Guide

|

This section contains 1,069 words (approx. 3 pages at 400 words per page) |

|